14.2. Points, Segments and their Properties¶

- File:

Points.ml

14.2.1. On precision and epsilon-equality¶

Geometrical objects in a cartesian 2-dimensional space are represented

by the pairs of their coordinates \(x, y \in \mathbb{R}\), which

can be encoded in OCaml using the data type float. As the name

suggests, this is the type for floating-point numbers, which can

encode mathematical numbers with a finite precision. This is why

ordinary equality should not be used on them.

For instance, as a result of a numeric computation, we can obtain two

numbers 0.3333333333 and 0.3333333334, both “encoding”

\(\frac{1}{3}\), but somewhat approximating it in the former case

and over-approximating it in a latter case. It is considered a usual

practice to use an \(\varepsilon\)-equality, when comparing

floating-point numbers for equality. The following operations allow us

to achieve this:

let eps = 0.0000001

let (=~=) x y = abs_float (x -. y) < eps

let (<=~) x y = x =~= y || x < y

let (>=~) x y = x =~= y || x > y

let is_zero x = x =~= 0.0

14.2.2. Points on a two-dimensional plane¶

A point is simply a pair of two floats, wrapped to a constructor to avoid possible confusions:

type point = Point of float * float

let get_x (Point (x, y)) = x

let get_y (Point (x, y)) = y

We can draw a point as a small circle (let’s say, with a radius of 3 pixels) using OCaml’s graphics capacities, via the following functions:

include GraphicUtil

let point_to_orig p =

let Point (x, y) = p in

let ox = fst origin in

let oy = snd origin in

(* Question: why adding fst/snd origin? *)

(int_of_float x + ox, int_of_float y + oy)

let draw_point ?color:(color = Graphics.black) p =

let open Graphics in

let (a, b) = current_point () in

let ix, iy = point_to_orig p in

moveto ix iy;

set_color color;

fill_circle ix iy 3;

moveto a b;

set_color black

Let us take some of the predefined points from this module:

module TestPoints = struct

let p = Point (100., 150.)

let q = Point (-50., 75.)

let r = Point (50., 30.)

let s = Point (75., 60.)

let t = Point (75., 90.)

end

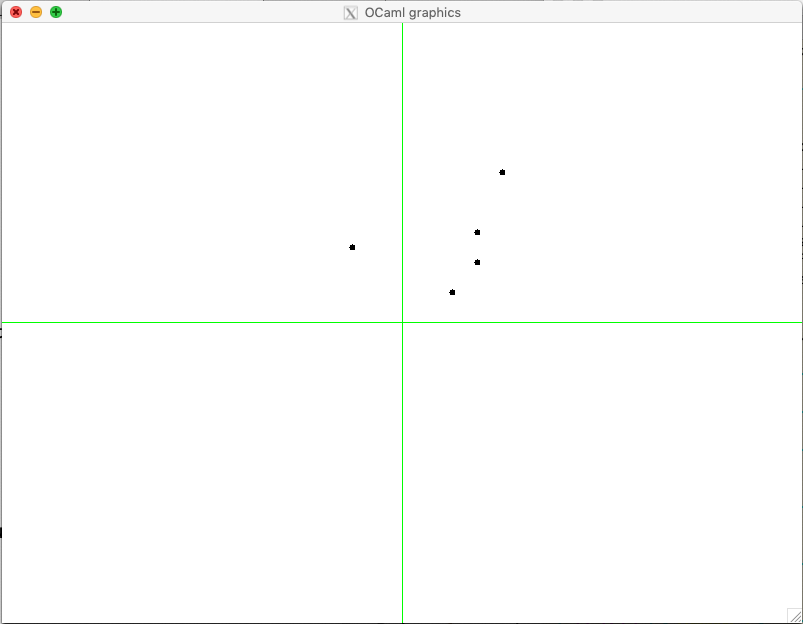

Drawing them as follows results in a picture below:

utop # open Points;;

utop # open TestPoints;;

utop # mk_screen ();;

utop # draw_point p;;

utop # draw_point q;;

utop # draw_point r;;

utop # draw_point s;;

utop # draw_point t;;

A very common operation is moving a point to a given direction, by adding certain x- and y-coordinates to it:

let (++) (Point (x, y)) (dx, dy) =

Point (x +. dx, y +. dy)

14.2.3. Points as vectors¶

It is common to think of 2-dimensional points oas of vectors — directed segments, connecting the beginning of the coordinates with the point. We reflect it via the function that renders points as vectors:

let draw_vector (Point (x, y)) =

let ix = int_of_float x + fst origin in

let iy = int_of_float y + snd origin in

go_to_origin ();

Graphics.lineto ix iy;

go_to_origin ()

Notice that, in order to position correctly the vector, we keep “shifting” the point coordinates relatively to the graphical “origin”. We do so by adding fst origin and snd origin to the x/y coordinate of the point, correspondingly.

The length of the vector induced by the point with the coordinates \((x, y)\) can be obtained as \(|(x, y)| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}\):

let vec_length (Point (x, y)) =

sqrt (x *. x +. y *. y)

Another common operation is to subtract one vector from another ot obtain the vector that connects their ends:

let (--) (Point (x1, y1)) (Point (x2, y2)) =

Point (x1 -. x2, y1 -. y2)

14.2.4. Scalar product of vectors¶

Imagine that we want to “turn” one vector in the direction of another. For this, we need to answer three questions:

- How can we calculate the value of the angle?

- How to perform the rotation?

- Which direction to turn?

The question (a) can be answered by computing the scalar product (often referred ) of the two points/vectors. By definition \((x_1, y_1) \cdot (x_2, y_2) = |(x_1, y_1) (x_2, y_2)|\cos{\theta} = x_1 \times x_2 + y_1 \times y_2\), where \(\theta\) is the smaller angle between \((x_1, y_1)\) and \((x_2, y_2)\).

Therefore, we can calculate the scalar product as follows:

let dot_product (Point (x1, y1)) (Point (x2, y2)) =

x1 *. x2 +. y1 *. y2

Assuming neither of the two vectors is zero, we can calculate the angle using the function acos from OCaml’s library:

let angle_between v1 v2 =

let l1 = vec_length v1 in

let l2 = vec_length v2 in

if is_zero l1 || is_zero l2 then 0.0

else

let p = dot_product v1 v2 in

let a = p /. (l1 *. l2) in

assert (abs_float a <=~ 1.);

acos a

14.2.5. Polar coordinate system¶

Rotations are very awkward to handle in the cartesian representation of points and vectors. They are much more convenient to peerform in the polar coordinate system, where each point/vector is represented by (i) the length \(r\) of the vector, and (ii) the radial angle \(-\pi < \phi \leq \pi\).

In OCaml, the value of \(\pi\) can be obtained as from the arctangent of 1, which is equal \(\pi / 4\):

let pi = 4. *. atan 1.

We encode polar point representations using a new datatype:

type polar = Polar of (float * float)

The following two conversions follow from the correspondence between cartesian and polar coordinates:

let polar_of_cartesian ((Point (x, y)) as p) =

let r = vec_length p in

let phi = atan2 y x in

let phi' = if phi =~= ~-.pi then phi +. pi *. 2. else phi in

assert (phi' > ~-.pi && phi' <=~ pi);

Polar (r, phi')

let cartesian_of_polar (Polar (r, phi)) =

let x = r *. cos phi in

let y = r *. sin phi in

Point (x, y)

Finally, we can express rotation by conversion from cartesian to polar coordinates and back:

let rotate_by_angle p a =

let Polar (r, phi) = polar_of_cartesian p in

let p' = Polar (r, phi +. a) in

cartesian_of_polar p'

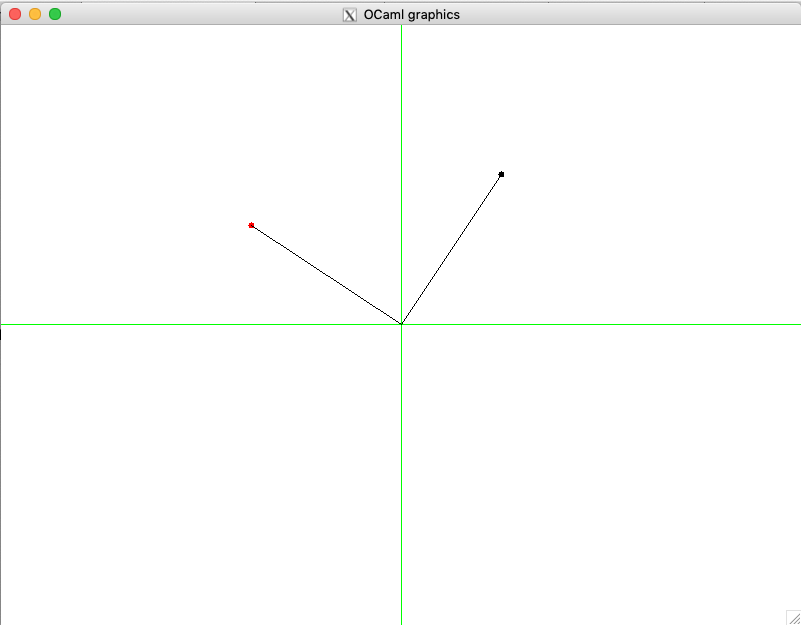

We can use this machinery to rotate by 90 degrees (i.e., \(\pi/2\)) the vector p to point in the new direction:

utop # clear_screen ();;

utop # draw_point p;;

utop # let p' = rotate_by_angle p (pi /. 2.);;

utop # draw_point ~color:Graphics.red p';;

utop # draw_vector p;;

utop # draw_vector p';;

14.2.6. Vector product and its properties¶

Vector product of two vectors (also known as cross-product) of two vectors \(p1 = (x_1, y_1)\) and \(p2 = (x_2, y_2)\) is formally defined as \((x_1, y_1) \times (x_2, y_2) = |(x_1, y_1)||(x_2, y_2)|\sin{\theta} = x_1 \times y_2 - x_2 \times y_1\), where \(\theta\) is an angle between the two vectors:

let cross_product (Point (x1, y1)) (Point (x2, y2)) =

x1 *. y2 -. x2 *. y1

As the cross-product cross_product p1 p2 it operates with a sine rather than cosine, it allows to determine the “direction”, in which in which one needs to rotate \(p1\) to approach \(p2\) in the closest way. Specifically, if the result of the cross-product is positive then, one should move in the counter-clockwise fashion, while if it is negative, \(p1\) is in the clockwise direction from \(p2\). Finally, if the product is zero, the two vectors are parallel and point in the same or the opposite directions:

let sign x =

if x =~= 0. then 0

else if x < 0. then -1

else 1

(* Where should we turning p2 *)

let dir_clock p1 p2 =

let prod = cross_product p1 p2 in

sign prod

Another famous mnemonics to remember the relation between the sign of the cross product of the vectors \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) comes from a so-called right-hand rule. You have come across this rule in the real lide while interacting with screws if you turn the screw counter-clockwise (think of rotating \(p_1\) to \(p_2\) the same way), the screw moves up (cross-product is positive); otherwise the screw moves down (cross-product is negative).

We can now employ the cross-product to know in which direction to rotate on vector to another:

let rotate_to p1 p2 =

let a = angle_between p1 p2 in

let d = dir_clock p1 p2 |> float_of_int in

rotate_by_angle p1 (a *. d)

Finally, given three points, p0, p1 and p2, one can use the operations of vector subtractions to determine in which direction the chain [p0; p1; p2] turns:

let direction p0 p1 p2 =

cross_product (p2 -- p0) (p1 -- p0) |> sign

The direction depends on the result of of the function above:

- If it is 1, the chain is turning turning right (clock-wise);

- If it -1, it is turning left (counter-clock-wise);

- 0 means there is no turn.

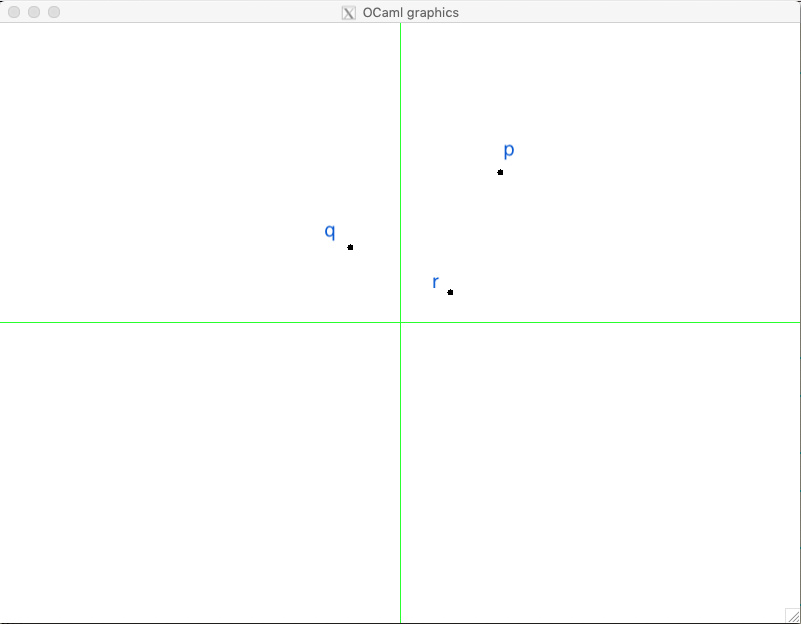

For example, for the following image, the result of direction q r p is -1:

14.2.7. Segments on a plane¶

From individual points on a plain, we transition to segments, are simply the pairs of points:

type segment = point * point

The following definitions allow one to draw segments using our plotting frameworks, and also provide some default segments to experiment with:

(* Draw a segment *)

let draw_segment ?color:(color = Graphics.black) (a, b) =

let open Graphics in

draw_point ~color:color a;

draw_point ~color:color b;

let iax, iay = point_to_orig a in

moveto iax iay;

set_color color;

let ibx, iby = point_to_orig b in

lineto ibx iby;

go_to_origin ()

module TestSegments = struct

include TestPoints

let s0 = (q, p)

let s1 = (p, s)

let s2 = (r, s)

let s3 = (r, t)

let s4 = (t, p)

let s5 = (Point (-100., -100.), Point (100., 100.))

let s6 = (Point (-100., 100.), Point (100., -100.))

end

14.2.8. Generating random points on a segment¶

It is easy to generate random points and segments within a given range f:

let gen_random_point f =

let ax = Random.float f in

let ay = Random.float f in

let o = Point (f /. 2., f /. 2.) in

Point (ax, ay) -- o

let gen_random_segment f =

(gen_random_point f, gen_random_point f)

We can exploit the fact that an point \(z\) on a segment \([p_1, p_2]\) and be obtained as \(z = p_1 + t (p_2 - p_1)\) for some \(0 \leq t \leq 1\). here, both addition and subtraction are vector operations, encoded by (++) and (--) correspondingly:

let gen_random_point_on_segment seg =

let (p1, p2) = seg in

let Point (dx, dy) = p2 -- p1 in

let f = Random.float 1. in

let p = p1 ++ (dx *. f, dy *. f) in

p

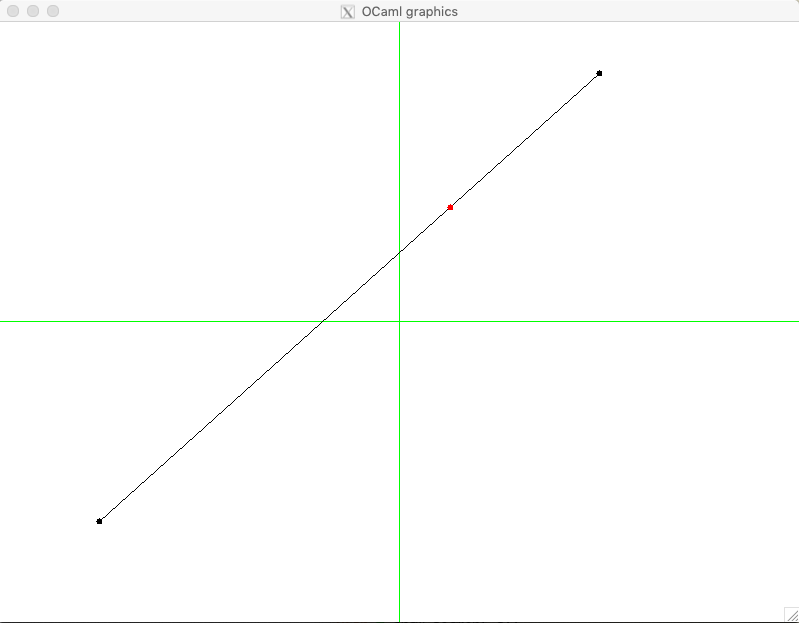

Let us experiment:

utop # clear_screen ();;

utop # let s = (Point (-300., -200.), Point (200., 248.));;

utop # let z = gen_random_point_on_segment s;;

val z : point = Point (51.3295884528682222, 114.791311253769891)

utop # draw_segment s;;

utop # draw_point ~color:Graphics.red z;;

14.2.9. Collinearity of segments¶

Two segments are collinear (ie., belong to the same straight line), if each of the points of one segment forms a 0-turn (i.e., neither left, nor right) with the two points of another segment. Therefore, we can check the collinearity of two segments s1 and s2 as follows:

(* Checking if segments are collinear *)

let collinear s1 s2 =

let (p1, p2) = s1 in

let (p3, p4) = s2 in

let d1 = direction p3 p4 p1 in

let d2 = direction p3 p4 p2 in

d1 = 0 && d2 = 0

A point p is on a segment [a, b] iff [a, p] and [p, b] are collinear, and both coordinates of p lie between the coordinates of a and b. Let us leverage thins insight using in the following checker:

(* Checking if a point is on a segment *)

let point_on_segment s p =

let (a, b) = s in

if not (collinear (a, p) (p, b))

then false

else

let Point (ax, ay) = a in

let Point (bx, by) = b in

let Point (px, py) = p in

min ax bx <=~ px &&

px <=~ max ax bx &&

min ay by <=~ py &&

py <=~ max ay by

14.2.10. Checking for intersections¶

Two segments s1 and s2 intersect if they

- collinear and have common points, or

- intersect on one point precisely.

The first case (a) can be checked by the following function:

let intersect_as_collinear s1 s2 =

if not (collinear s1 s2) then false

else

let (p1, p2) = s1 in

let (p3, p4) = s2 in

point_on_segment s1 p3 ||

point_on_segment s1 p4 ||

point_on_segment s2 p1 ||

point_on_segment s2 p2

The case (b) is more tricky, and we use the following insight. Two segments intersect if each one of them straddles the line that another segment lies on. A segment [p1; p2] straddles a line if point p1 lies on one side of this line, whereas p2 lies on another side. We can check this by using the mechanism for determining turn directions, developed before:

(* Checking if two segments intersect *)

let segments_intersect s1 s2 =

if collinear s1 s2

then intersect_as_collinear s1 s2

else

let (p1, p2) = s1 in

let (p3, p4) = s2 in

let d1 = direction p3 p4 p1 in

let d2 = direction p3 p4 p2 in

let d3 = direction p1 p2 p3 in

let d4 = direction p1 p2 p4 in

if (d1 < 0 && d2 > 0 || d1 > 0 && d2 < 0) &&

(d3 < 0 && d4 > 0 || d3 > 0 && d4 < 0)

then true

else if d1 = 0 && point_on_segment s2 p1

then true

else if d2 = 0 && point_on_segment s2 p2

then true

else if d3 = 0 && point_on_segment s1 p3

then true

else if d4 = 0 && point_on_segment s1 p4

then true

else false

14.2.11. Finding intersections¶

Sometimes we need to find the exact points where two segments intersect.

In the case of collinear segments that intersect this is reduced to the enumeration of four possible options (at least one end of some segment should belong to another segment).

The case of non-collinear segments [p1; p2] and [p3; p4] can be solved if each is represented in a form \(p_1 + t r\) and \(p_3 + u s\), where \(t\) and \(s\) are the vectors connecting the end-points of each segment correspondingly, and \(t\) and \(u\) are scalar values ranging from 0 to 1. We need to find \(t\) and u such that \(p_1 + t r = p_3 + u s\). To solve this equation (which has two variables), we need to multiple both sides by, using the cross-product, by either \(r\) or \(s\). In the former case we get \((p_1 + t r) \times s = (p_3 + u s) \times s\). Since \(s \times s\) is a zero vector, we can get rid of the variable \(u\), and find the desired \(t\) as in the implementation below:

let find_intersection s1 s2 =

let (p1, p2) = s1 in

let (p3, p4) = s2 in

if not (segments_intersect s1 s2) then None

else if collinear s1 s2

then

if point_on_segment s1 p3 then Some p3

else if point_on_segment s1 p4 then Some p4

else if point_on_segment s2 p1 then Some p1

else Some p2

else

let r = Point (get_x p2 -. get_x p1, get_y p2 -. get_y p1) in

let s = Point (get_x p4 -. get_x p3, get_y p4 -. get_y p3) in

assert (not @@ is_zero @@ cross_product r s);

(*

(p1 + t r) × s = (p3 + u s) × s,

s x s = 0, hence

t = (p3 − p1) × s / (r × s)

*)

let t = (cross_product (p3 -- p1) s) /. (cross_product r s) in

let Point (rx, ry) = r in

let p = p1 ++ (rx *. t, ry *. t) in

Some p

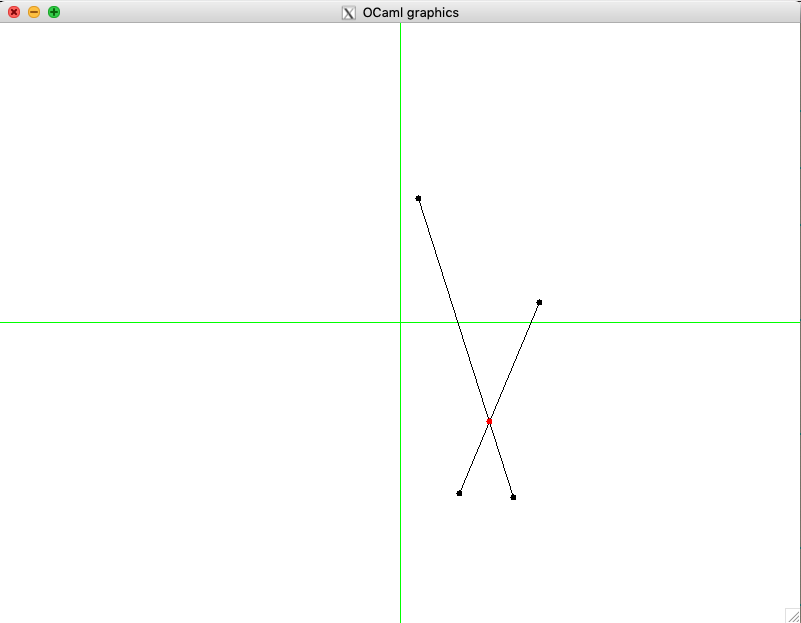

We can graphically validate the result:

utop # let s1 = (Point (113.756053827471192, -175.292497988606272),

Point (18.0694083766823042, 124.535770332375932));;

utop # let s2 = (Point (59.0722072343553464, -171.91124390306868),

Point (139.282462974003465, 20.2804812244832249));;

utop # draw_segment s1;;

utop # draw_segment s2;;

utop # let z = Week_01.get_exn @@ find_intersection s1 s2;;

utop # draw_point ~color:Graphics.red z;;